The Problem with American Emergency Alerts

In a world of self-driving cars and human-like chatbots, shouldn't the best technologies would be used for life-saving applications?

4 nights ago I was awoken by a familiar but unpleasant noise. Anyone who has experienced it vividly remembers the distinct, jarring blaring of an emergency alert forcing its way through your silenced phone. I squinted at my phone for the below message to sear my eyeballs.

BLUE ALERT ISSUED FOR TERRAN GREEN FOR INJURY TO AN OFFICER BY HARRIS COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE. SUSPECT IS A 34 YEAR OLD BLACK MALE DRIVING A BLUE FORD ESCAPE. TXLP: SVJ6590. GREEN WAS LAST SEEN WEARING GRAY SHIRT, BLACK SHORTS. ANYONE WITH INFORMATION IS URGED TO CALL 9-1-1.

I did what I usually do when when an emergency alert comes through: I ignored it and went back to my business. I put my phone back on the charger, rolled over, and went back to sleep. I wasn’t the only one.

There’s a reason there are thousands of guides online on how to disable emergency alerts on your phone. Their poor implementation has made many ignore them— the exact opposite of what an emergency alerting system should do. Not only does this render the alerts useless, it does something much worse: it builds the habit of ignoring them.

Once a habit is built, it’s incredibly difficult to break. This is especially true with technology. Even when the emergency alert system is improved, it will continue to be ignored to the detriment of public safety.

The Emergency Alert System (EAS) was established in 1994 as a way to communicate emergencies to the general public1. The EAS sends emergency warnings via cable and radio. You’ve seen the EAS in use if you’ve seen a severe weather warning scroll across the TV when you’re watching.

Clearly, cable and radio are no longer our primary mode of communication. In 2012, a complementary notification system called Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) was put into operation that sends emergency notifications to smartphones2.

The WEA lets authorized public safety officials broadcast emergency alerts to smartphones in locally affected areas. These alerts are sent to WEA-capable phones via wireless carriers based on a geographic location specified by public safety officials. These alerts are sent to your device based on local cell towers and then use your smartphone’s GPS to make sure you’re properly within the designated area.

WEAs are split into the following categories:

AMBER Alerts (missing child alerts)

Emergency Alerts

Public Safety Alerts

Test Alerts

National Security Alerts

All but National Security Alerts can be disabled by the owner of a phone. If the President wants to wake you in the middle of the night, he can and there’s nothing you can do about it. If you’re holding out thinking you might be thrown into a movie-like scenario where the President needs specifically your help, there’s still hope.

Let’s take a look at my middle of the night example above to identify two major issues with the current emergency alert implementation.

The categories aren’t clear.

Where does a “blue alert” fit in? Is it an Emergency Alert or a Public Safety Alert? What if I want to disable blue alerts but I still want alerts about wildfires or tornadoes? Which categories do I disable and enable?

The alert is super unlikely to be applicable to a large majority of recipients, especially at 2 AM.

Harris county is in Houston. I live in Austin 170 miles away. That means likely phones within a 170 mile radius (or greater) away from Houston were sent that blue alert. Millions of people were awoken.

I understand this was because someone armed and dangerous was on the loose. It’s better to over communicate than cause someone who needs to know to be left in the dark; however, in a world of self-driving cars and human-like chatbots it seems silly that we’re basing who needs to know about an emergency solely on a (largely arbitrarily determined) geographical region.

At this point, it’s better to disable government emergency alerts altogether and subscribe to a more accurate local solution for region-based alerts.

I’ve read numerous Reddit threads contemplating disabling these notifications because they aren’t applicable. I, myself, have gotten many AMBER Alerts over the past year for San Antonio (100 miles away). All the comments about disabling the alerts are the same: “A notification disrupting your day is a small sacrifice to possibly help a kid being kidnapped”.

The commenters are right, but they’re missing the point. The complaint isn’t about the emergency alerting system— it’s about pointless alerts. I don’t think anyone thinks government emergency alerts to smartphones are a bad idea. However, constant pointless alerts create a noisy notification system waiting to be disabled — at which point it ceases to be an alerting system at all. With modern technology, there’s no excuse for this.

As a quick aside, digging into the 2021 AMBER Alert report shows why I might be a bit sensitive to these pointless government emergency alerts as a Texan.

AMBER Alerts were originally named after Amber Rene Hagerman, a girl who was abducted in Texas. Many states had their own regional variant of the alert name in memory of children kidnapped in their state. It’s now a backronym for “America's Missing: Broadcast Emergency Response”.

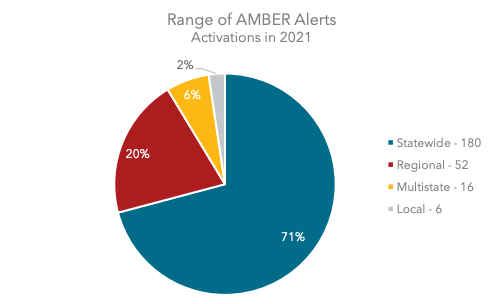

To reiterate, local emergency services determine the range of an Alert. An infographic from the report shows 71% of alerts are statewide. Texas is a huge state. This explains the AMBER Alerts I’ve received from El Paso (580 miles away).

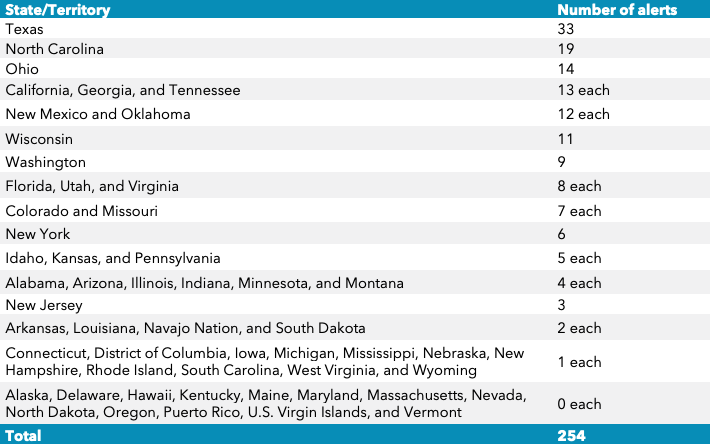

On top of that, Texas far-and-away has the most AMBER Alerts reported according to the table from the report shown below. Part of this is because Texas is a large state both in population and area, but California, a state with a larger population and also a large area, has about a third of the AMBER Alerts.

I’m not sure what’s causing this massive number of Alerts, but it explains why the local Texas communities are annoyed by them. The Alerts also probably feel extra pointless to Texans because a statewide Alert has a high chance of being 600 miles away.

How can it be better?

I think there’s no excuse for not using top-of-line solutions for problems that are potentially life threatening for a great deal of the public. A few suggestions I have for making this happen:

Emergency alerts should filter by more than location and tap into more phone features.

They could use Sleep Focus, Home location, etc. to better understand a person’s situation. Someone who is asleep in their bed doesn’t need the same alerts as someone who is out on the road at 2 AM.

The emergency alert system already uses our smartphone’s GPS and not just cell towers. It can tap into other phone features for more accurate alerting. The WEA system can push an alert to your phone and let your phone choose to display or ignore the alert. This prevents extraneous information from being supplied to the government; instead, information you’ve already given to your phone will be used for more accurate alerting.

We could even use machine learning algorithms to examine all alerting factors (your current state, type of alert, your location, etc.) to accurately determine if an alert should be displayed.

This algorithm could even be used to determine if more features of the phone should be used in the situation.

When it comes to life-saving solutions, we should use more than just short notifications.

It’s great to notify the public of an issue, but what if your phone could automatically display an evacuation route for you if necessary? What if it could be determined that you’re in danger and your precise location could be made available to emergency services such as firefighters and EMTs?

Let’s take the recent Maui wildfires as an example. Public safety officials were criticized for not sounding a siren when the wildfires were quickly spreading. They answered that sirens would have caused more death by sending citizens toward the wildfires. The sirens were usually used as a tsunami warning for which the protocol is to move inland. In this scenario, everyone would have wanted to move toward the water.

What if an alert could have been sent to residents on Maui with an evacuation plan included in the alert via Google or Apple Maps? It could have located the quickest way for residents to get to a safe area and guided them there step-by-step. It also could have pinged emergency services for a more accurate understanding of where residents who were in trouble were located.

I admit these are ambitious features to add to an emergency alerting system, but they could be done. They would require collaboration between the government and private companies, but the two major players aren’t new to collaborating with emergency services for public safety (Google and Apple).

Other downfalls are added complexity to a critical emergency system and making it compatible with smartphones that may not have the capabilities required for my suggestions above. It also requires training and maintaining a machine learning model to perform the above operations.

Maybe I’m getting ahead of myself with these suggestions. I likely don’t understand the nuance involved in the emergency alert system, but it baffles me to see a life-saving system use anything but the best. When it comes to things the government should supply for you, shouldn’t safety be the highest priority?

If you have a simpler solution to improve emergency alerts and fix the habitual ignoring of them let me know.

We need to make changes to our emergency alert system, and we need to do it quickly. Old habits die hard and the longer we wait to improve our alerts, the harder it will be to make the improvements.

Last week on Society’s Backend

Join the community

Make sure you’re subscribed (it’s free!) to chat with other readers. A subscriber chat is coming soon.

Connect with me

I love writing, but I love conversing about these topics even more! Connect with me on LinkedIn, Twitter/X, and YouTube.

As a thank you for reading to the very end, here’s half off a subscription for Society’s Backend forever.

https://www.fcc.gov/emergency-alert-system#block-menu-block-4

https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/wireless-emergency-alerts-wea