Call of Duty has a data science problem

A lesson in why data science matters and what makes it so complex

This is an everyday, real-world example of why data science is important and what makes it difficult. It might not seem like this is relevant to machine learning and AI, but ML and AI are just data science problems. Getting models and AI systems right requires understanding the underlying data and using it properly.

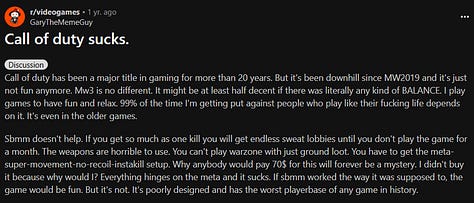

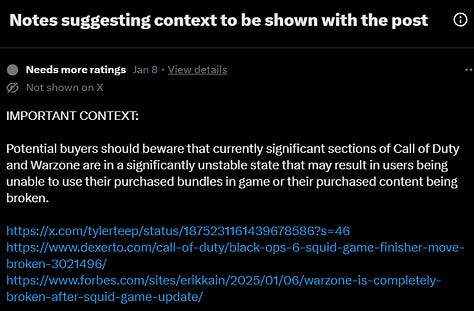

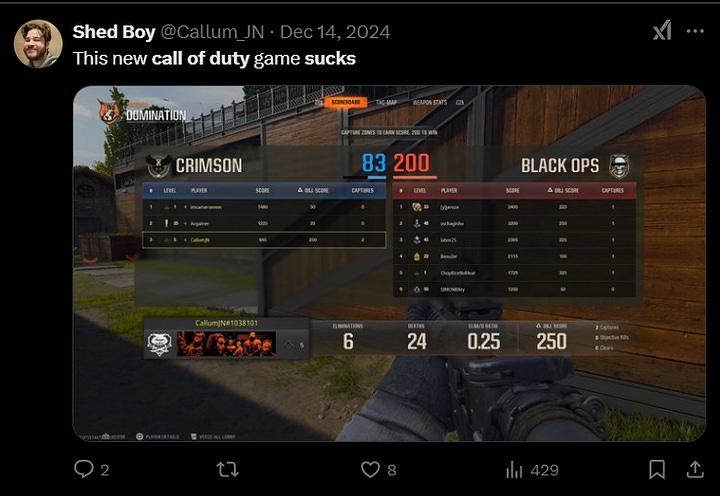

There’s been a lot of drama about Call of Duty’s latest release, Black Ops 6, because professional and casual players alike are complaining about core game mechanics and the overall game experience having degraded from previous iterations in the Call of Duty franchise. Gamers reason this to be the result of bad game development when in actuality the bad game development they’re referring to is just a symptom of the real issue: bad data science.

For those who aren’t familiar with Call of Duty, it’s the second highest grossing video game franchise in the world. It’s an online, multiplayer first-person shooter game with an annual release cycle. The annual release cycle is a major driver behind player complaints. They’re frustrated that annual releases seem intended to profit from players. It forces them to pay $70 each year for a new game while the quality of the game degrades due to a rushed release schedule.

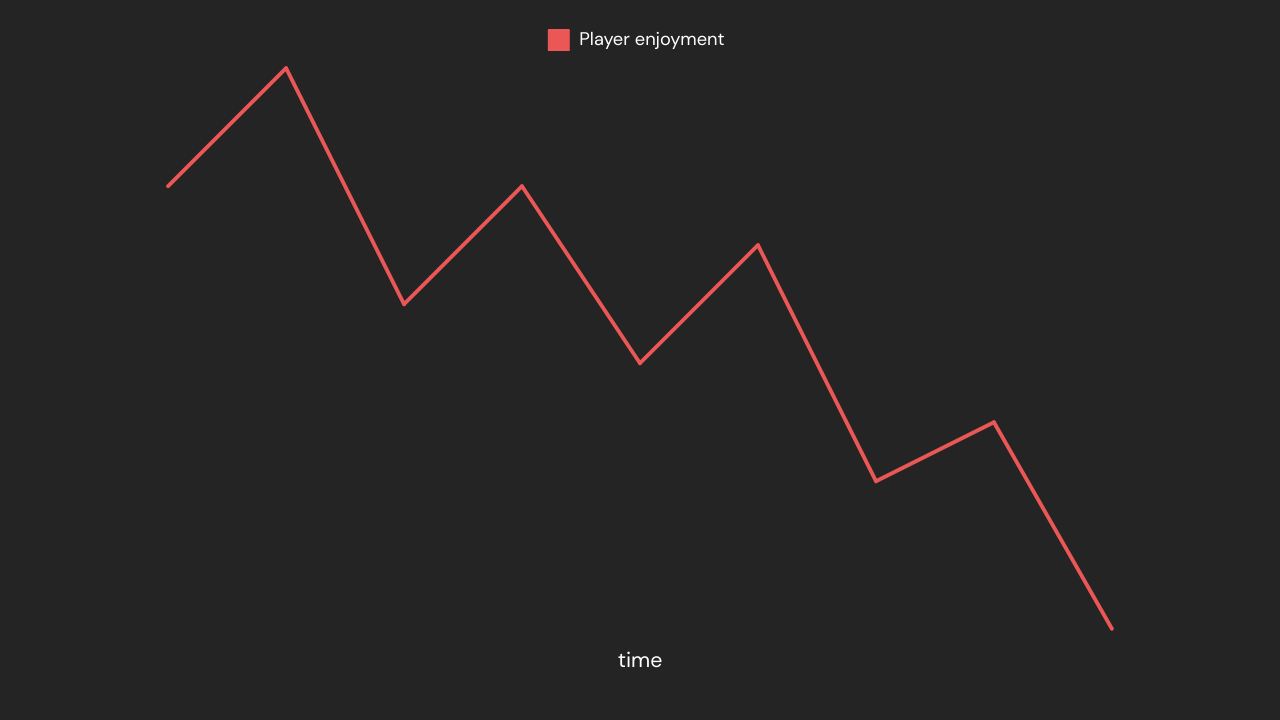

While players complain the companies behind Call of Duty claim metrics show the game is more enjoyable for players. So, how is it possible that metrics can show greater player enjoyment while the actual players are increasingly more frustrated with each game release? Herein lies the data science problem.

Companies use data to drive business decisions. This is very similar to machine learning where data is fundamental to decisions made to improve model performance. To make good business decisions, companies need high-quality data. To build great models, we need high-quality data. In both cases, data is useless if it doesn’t show accurately show us the signal we’re looking for.

The data collected by businesses is far from simple. Not only do businesses need to collect the correct data (they’re collecting data that will tell them the data they’re looking for), they also need to insure the data is interpreted properly (is the data actually telling us what we think it is?). Let’s get into some specifics of the Call of Duty situation to exemplify this.

Disclaimer: Call of Duty developers haven’t actually released the exact data they use to make decisions related to game development, but they have filed patents and released whitepapers with some information pertaining to this. I’ll be using the information from a skill-based matchmaking whitepaper, a microtransactions patent, a patent for equalizing player skill levels in real-time, and my knowledge of data science to infer the information below.

We can explore some specific examples of the metrics Call of Duty is likely using to support their claims. They claim the playing experience is more enjoyable, but how are they measuring that? To use data to draw conclusions, a company must determine what constitutes success and the metrics that will tell them whether its been reached.

The first example we can take a look at is the most apropos, as it's very relevant to the recent decline of AAA game enjoyment and is the most frustrating for the Call of Duty community. This example is using profit as a metric for success. The mindset here is: If the players are spending money on the game, they must be enjoying it. Therefore, metrics measuring profit are collected and the game is developed to maximize those values.

The problem with this is there is no definitive evidence that profit correlates to a better player experience. Instead, this objective is usually motivated by shareholders and is a success metric specifically designed to satisfy them–not the players. While profit is important for a business to succeed, solely optimizing for profit often comes at the decline of other factors that contribute to an enjoyable game experience. Understanding this effect is especially important for long-term franchise health.

Regarding Call of Duty, measuring and optimizing profit is a terrible way to understand the player experience. Profit metrics are more likely measuring how effective the game is at manipulating consumer psychology to drive players to make purchases or how well they’re optimizing the pricing of cosmetics to maximize the amount players spend.

In modern gaming, optimizing for these factors is an excellent way to alienate even the most dedicated communities. Gacha games and microtransactions have put a bad taste in gamers’ mouths because they tend to be exploitative while often providing a worse game experience. Take Diablo Immortal as an example. It’s a free-to-play game that uses microtransactions to gate player progression. This aggressive cash grab alienated the game’s core audience.

Think about it for yourself: If your favorite game was riddled with microtransactions and aggressive funneled you toward making in-game purchases after you had already spent $70 to buy the game, would it remain your favorite game for long? This is what we see happening with a lot of the Call of Duty community.

Let’s take a look at a more probable example of a metric Call of Duty measures and optimizes to understand player enjoyment: Time spent playing. Common sense dictates that metric correlates more with player enjoyment than profit optimization but that doesn’t mean it’s an accurate metric. While players will tend to come back to a game they enjoy, it doesn’t mean time spent playing a game shows they enjoyed it. Players can (and definitely do) experience “regrettable playing time” while playing the newest Call of Duty.

There’s a theory that the newest Call of Duty game manipulates game factors such as spawns, bullet damage, and aim assist (if you aren’t familiar with that terminology basically it just means changing difficulty levels on the fly only for specific players) to maximize the number of games a player plays. The theory claims these factors are manipulated to let a player have a long kill streak followed by many failures followed by another kill streak and so on. This gives the player a dopamine rush and then a negative experience to make the next dopamine rush even greater. The dopamine rushes keep the player chasing more.

I’m not saying this theory is entirely true but it isn’t implausible. This theory does paint a good picture of why measuring playing time as a metric for player enjoyment isn’t correct. “Regrettable playing time” isn’t successfully captured by optimizing for playing time even though it’s crucial to understanding whether a game is providing an enjoyable experience.

Similar to optimizing for profit, this is another metric that fails to capture long-term impact. Regrettable playing time is crucial for long-term franchise health because sales within a video game franchise are generally dictated by the games previous to it. Fans trust the next game to be good because they enjoyed the past games. Failures within a game are often seen in the sales of the next.

Of course, there’s no way to verify these examples without having the actual metrics Call of Duty uses to understand their player base. Their metrics are likely a lot more nuanced than the simple examples I provided, but the principles behind the data remain the same. When any company states a claim is supported by data when everything else seems to show the opposite, it reeks of a data science problem.

This is understandable because data is complex. There’s a reason that “data scientist” is a job of its own. These are people who spend all their time interpreting and analyzing metrics to make business decisions. When the metrics used to make these decisions are collected or interpreted incorrectly, they fail to be useful.

Now I bring this back to machine learning and AI which is fundamentally because it’s data science. That’s why those working in ML/AI are often called data scientists. They’re generally not analyzing business analytics, but they are collecting, manipulating, and using data to train models and achieve a specific outcome. Just like the data scientists analyzing business analytics, those working with machine learning data need to understand its complexities if they are to make it useful.

Let me know what you think! If you have any questions, leave them in the comments. Here’s a link to the YouTube video that originally got me thinking about this. It’s really interesting to hear what Call of Duty professionals have to say about the new game:

Thanks for reading!

Always be (machine) learning,

Logan